True or False?

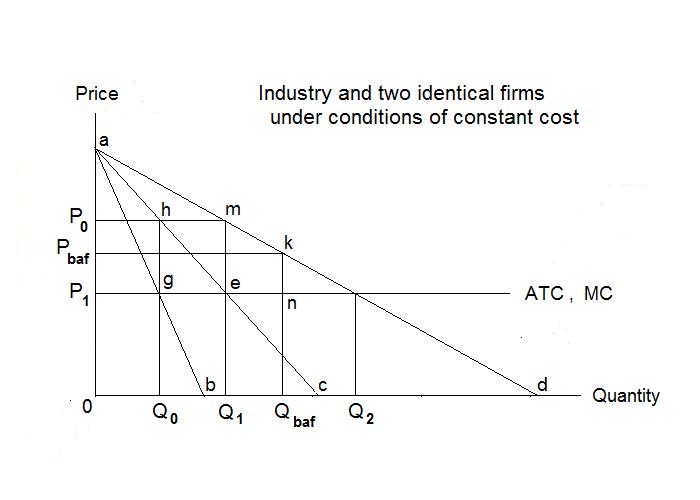

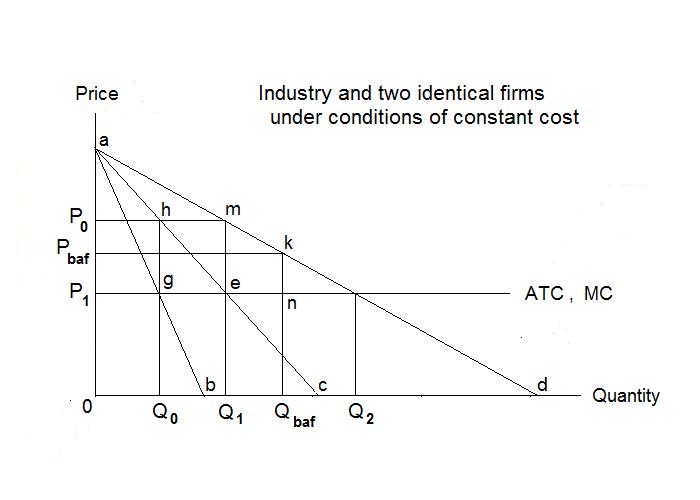

The statement is true. Consider the Figure below which represents both of the identical firms and the industry.

Both firms have constant average cost and, as a result, their marginal costs are equal to their average costs at the output price P1. The industry demand curve is given by the line a d and each firm's demand curve under a collusive arrangement in which they share the industry output equally is given by the line a c which, it turns out, is also the inustry's marginal revenue curve. Each firm's share of the industry marginal revenue is given by the line a b . Were the firms to successfully collude, they would charge the price P0, with each setting its output at Q0, thereby producing an industry output of Q1. Each firm would earn excess profits equal to the area of the rectangle P0 h g P1, with the industry excess profit being P0 m e P1. Given that average costs are constant at all levels of output, one firm could break the collusive agreement and chose a price slightly below P0 thereby grabbing the entire industry output. Suppose, strictly for the sake of illustration, the break-away firm chooses the price Pbaf . It will now sell the quantity Qbaf , earn profits equal to Pbaf k n P1. The other firm, which will now not be selling any output, has no alternative but to reduce its price below Pbaf , in which case it will now sell the total industry output and the original break-away firm will sell nothing. That firm now has no alternative but to again reduce its price. The price cutting will stop when the price has been reduced to P1 and the two firms each sell the output Q1, with the industry output being Q2 and both firms earning zero excess profits. The result in this case is the socially efficient one. We have to assume here that consumers randomly choose which firm to buy from when both are selling at the same price and that, on average, half of the consumers will buy from one of the firms and half will buy from the other. This equilibrium is called a Bertrand equilibrium, named after the French mathematician François Bertrand (1822-1900). It is also a Nash equilibrium as can be seen from the Table below.

| Firm #2 | |||

| Collude | Do Not Collude | ||

| Firm #1 | Collude | (monopoly profit , monopoly profit) | (out of business , all profits) |

| Do Not Collude | (all profits , out of business) | (zero profit , zero profit) | |

If Firm #2 chooses to collude, Firm #1's best option is to not collude. And if Firm #2 chooses not to collude, Firm #1's best option is to not collude. This is identical to the situation faced by Firm #2---its best option is not to collude, regardless of which option Firm #1 chooses. This assumes that going out of business is at least as bad as earning zero excess profits.

Unfortunately, there are reasons why this equilibrium is unlikely to occur in the real world, unless it is established by government intervention. Costs being constant, new firms will enter whenever there are excess profits, so there is no reason for a duopoly to arise---the most reasonable result would be many firms operating under perfect competition. A second problem is the constant cost assumption. Are there not fixed costs? If so, there would be only one firm in the industry because average total cost would fall continuously as the firm's output increased. Finally, there are unlikely to be many situations under which the firms produce an identical product---in most cases services are provided along with the commodity produced, and it is reasonable to suppose that firms have differing abilities to provide these services.